Saints or Legends?

The concept of Sainthood and the practice of venerating the icons and relics of Saints is foreign to most Protestants. Prior to becoming Orthodox, I found it to be a strange practice, associated with folk religion or syncretism. To be sure, it was a significant hurdle I had to cross upon entering the Church, so if you are an inquirer to Orthodoxy and are reading this, know that you are not alone.

Part of the reason that the concept of sainthood and the veneration of Saints is so confusing to Protestants, and especially in churches which are open to “moves of the Holy Spirit” is because they lack the works that Jesus said his followers would do. They believe that every Christian is already a saint and there is no distinction between saints and Saints. All of us have access to the Holy Spirit. All believers could work miracles, in theory. There is a mentality that exists that if I go to church enough, and sing and pray hard enough, and have my quiet times, and show up at the right revival services, and if I fast just right or do any combination of these things, stuff will happen. There is much made of healing services or those who work miracles in Protestant circles. Without a doubt, I have seen God’s mercy intervene in the lives of people, but the “greater works” have been elusive, at least where I’ve been hanging out. I realize that I am painting with broad strokes here, but it is a generalization that is founded on many years of experience in a variety of heterodox churches. From my current Orthodox perspective, I can see that if there were a continuity of tradition from apostolic times, and the tradition of ascetic and holy living had been in some way communicated throughout the latter generations, there would not be such a deep hunger for manifestations of the Holy Spirit because they would be accessible and experienced through the life of the One Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church.

For Orthodox believers, every time we walk into the church to attend the services of Divine Liturgy we are participating in the greatest miracle of all—The celebration of Christ’s death, burial, and resurrection. Through bread and wine, which becomes the body and blood of Christ, the recipients of this mystery are thus united with him in the sacrifice. From this celebration of the eucharist, all other miracles spring forth. We are driven to obedience by our desire to participate in the Divine Mysteries, and in so doing are motivated to holy living. Not everyone is in the same place, of course, and it takes a long time, but theosis is possible and the workings of great miracles as a result is not a foreign concept in the Orthodox faith. Stories of these who have achieved this level of theosis are considered Saints, and make up the mosaic of the picture that forms this faith. Accounts of men and women who have devoted their entire lives to prayer and have manifested great miracles abound in this tradition. I have heard stories of miracles from living saints who are ministering even today—hearing confessions, counseling the faithful, and speaking words of such clairvoyance it can only be through the Holy Spirit. These Christians are so humble and quiet about their work that they would not want to be mentioned publicly, and it is usually after their deaths that we begin to hear the extent of their ministry. Such stories are countless, and it is difficult to land on specific examples because they are all so wonderful, and frankly, incredible.

It is the “incredible part” that causes a problem. “Protestant me” could accept the stories of Christ’s miracles because He is God incarnate, and I could accept the miracles of the apostles because they were with Christ and the things they did were written in Acts. But because of the western mindset and the doctrine of Sola Scriptura, if it is not written down in Scripture (the 66 books that were accepted by the Reformers), then to my mind it fell under the category of “legend,” like King Arthur, Robin Hood, or Big Foot—stories that at one time may have had a grain of truth to them, but have been so embellished over time that the story is no longer credible. So to the Protestant mind, the Orthodox faith appears childish, ridiculous, or backward, and certainly not something an educated, intelligent person could build a religious life upon. But once on the inside of Orthodoxy, I began to understand that these stories are not only true, but they are alive and still being added to even today by modern, living Saints. They constitute the “greater works than these (John 14:12)” that Jesus spoke about. By no means were his works limited to his 12 apostles or the 70 that were sent out, but were bestowed upon anyone who would desire to enter into that oneness with Christ through the ascetic life that brings about Theosis.

One hurdle a Protestant must cross is that of the Saints themselves and the incredible miracles that accompany them both in life and death. These men and women live lives of such holiness that their works continue after their death, and the faithful believers become the beneficiaries of their continued intercessions for them. This conflicts with the heterodox notion of death and the afterlife completely. One would never consider praying to Mary or the Saints because they are DEAD. That they no longer live in the body may mean that their spirit is intended for resurrection when Christ returns, but in the meantime there is nothing that they can do for us and to ask for their help constitutes conjuring, necromancy, or idolatry.

Orthodoxy, on the other had, takes seriously the words of Christ when he says, “He who believes in me will NOT DIE but have eternal life. (John 3:16).” Thus, we can accept when an Orthodox believer reports receiving healing from cancer at the hands of physician who visited her in a dream, (St. Luke the Blessed Surgeon), or of a midwife who helped deliver a woman of the pain of abuse (Blessed Olga of Alaska), or of a man who was miraculously healed from complete paralysis when the clothing of a reposed monk was laid on his bed shortly after his bodily death. (St. Nectarios of Aegina)1 All three of these examples are from the 20th century. All of these miracles occurred after the repose of the individuals—after their physical death. Sadly, for all of my life I was told by Protestant teachers that such miracles as that of St. Luke or Mother Olga were demonic manifestations designed to distract believers from Christ. The miracle of St. Nectarios might have been accepted but without explanation. To my great joy, however, I have since learned that it is Christ who is working through these great Saints, precisely because they have so completely emptied themselves and become one with Him that they are able to continue to intercede on behalf of the world, and at times intervene in the very lives of individuals.

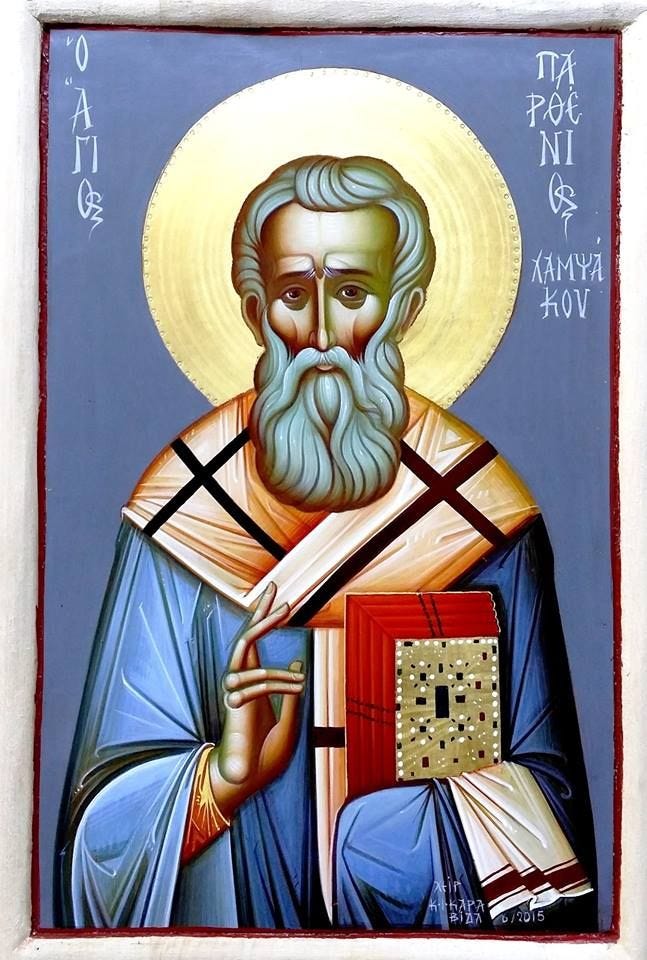

The day I am writing this is Feb. 20, 2023, and on the Julian calendar it is Feb. 7. I enjoy reading the lives of the saints daily from The Prologue of Ohrid and today’s saint is Saint Parthenius, Bishop of Lampsacus on the Hellespont. He is a perfect example of what is meant by theosis - that oneness with Christ that is so powerful that he worked miracles as great as those of the Apostles.

Parthenius was the son of a deacon from the town of Melitopolis. As a child he remembered well the words of the Gospel and endeavored to fulfill them. He settled near a lake, where he fished. He then sold the fish and distributed the money to the poor. By God’s providence he was chosen as Bishop of Lampasacus. He cleansed the town of paganism, closed the idolatrous temples, built many churches and strengthened believers in the Faith. Through prayer, he healed every manner of illness and was particularly powerful over evil spirits. On one occasion, when he wanted to cast out an evil spirit from an insane man, the evil spirit begged him not to do so. Parthenius said to him: “I will give you another man whom you can enter, and in him you can dwell.” The evil spirit asked him: “who is this man?” “I am that man,” replied the saint. “Enter and dwell in me!” Upon hearing this, the evil spirit fled as though burned by fire, crying out: “how can I enter into the house of God?” St. Parthenius lived a long time and through his work manifested an abundant love for God and man. Parthenius entered into the eternal rest of Christ in the fourth century. (p. 158)2

I chose this story because it illustrates well my point, but I could have turned to any page for similar stories. Every single day has its saints who are commemorated in the church and bear witness to such holy perfection in Christ. In the life of St. Parthenius, we see a man who had so united himself to Christ that the demons recognized his holiness and fled from him. What confidence in Christ he had to be able to offer himself to the demons, knowing full well that they could not bear his presence!

This, in its most practical sense, is the meaning of theosis—of being crucified with Christ so that I no longer live but Christ lives in me. That we as human beings become living icons of Christ himself, with access to the paraclete, the Holy Spirit, who will work God’s will through and among us.

So how does this relate to the veneration of icons and relics?

It is quite simple. If we come to the place where we can accept that an icon of Christ is a valid depiction of the incarnate Son of God, or that a representation of the Theotokos (Mary) is a means by which we are directed to Him by her very presence and posture in the icon, then it is the same with every icon of every Saint. I asked my Godmother about this very thing at the beginning of my inquiry, and her answer was very succint. She said, “Every icon is an icon of Christ,” and in that simple phrase, I understood the profound truth of the statement. That we are in Him and he is in us. It is out of love and devotion to Christ that I walk up to an icon of the patron of our parish, St. Herman of Alaska, to bow, make the sign of the cross, kiss the icon, and cross myself again. Or that I go around the church to venerate my own patron saint, Mary of Bethany, or St. George the Great-martyr and Victory-bearer, my husband’s patron saint. But ultimately my heart is filled with love for Christ, and these men and women who have united themselves with Him deserve my respect, gratitude, and veneration for the example they have set and for the intercessions they continually make on our behalf before the Throne of God. It is not the icon of wood and paint that is anything by itself. Rather we can trust that because the Saints are now outside of time and before the throne of grace, and able to see and sympathize with our earthly condition, the veneration is passed on through the icon to the Saint. It is as though the kiss applied were a stamp on a heavenly letter, asking for help.

Protestant me, who is shrinking by the day, still has some questions about relics, and you may as well. Orthodox me would put it this way: If you could possess an item, such as an article of clothing or a cup or a lock of the hair of a particular Saint such as the Theotokos, or Peter, or St. Paul, would you turn it down? Would you cherish it? Would you honor it by placing it in a special box or under a glass case? Of course you would! Why? Because that item is at the very least a precious reminder of the reality of its owner’s existence, and at most, bears the wonder-working Grace that was in that person during their lifetime. In the first case, we who love are loth to relinquish things that have value to us concerning our loved ones. In the second case, these relics still bear the miracle-working power of the saint himself, and many experience healings and other miracles in their presence. Orthodox Christians believe that objects and places and bodies (both alive and reposed), can be and are holy. For instance, the belt of the Theotokos is venerated as a holy relic at Mt. Athos, and I have been told by one who has seen it that the grace of God is powerfully present there and is felt by those who come to see it. To us it is not just a piece of cloth—it was the clothing of the very Mother of God and this is not taken lightly. Therefore, relics and icons fall in the same category with regards to veneration. They become the windows and portals by which we can express our deep affection for the Saints who have loved Christ with all of their hearts, souls, and minds, who have loved their neighbors as themselves, and who continue to love the Body of Christ through their prayers and intercessions for us and the whole world, even though they are absent from the body.

Graphical User Interfaces, GUIs, “icons”

I promised in part 1 of this series to come back to that modern notion of the icon such as we have on our phones—the graphical user interface (GUI) that one clicks to access the power behind it, such as your web browser icon. I have found this to be an extremely accessible analogy for me in understanding the spiritual nature of icons. When we venerate and ask a Saint for help, in much the same way, we are accessing a graphical user interface tool to reach beyond ourselves to one who has direct access to Christ and the Theotokos. I Corinthians 13:12 (ESV) says,

“For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known.”

These who have gone before stand unimpeded in the glory of Christ, in full knowledge of all that awaits us. They have run and finished the race. Should we not love them and seek their help?

Through the prayers of our Holy Fathers, Lord Jesus Christ our God, have mercy on us and save us. +

Amen.

The movie Man of God tells the story of St. Nektarios of Aegina, including the story of his death and the miraculous healing of the man in the hospital bed next to him.

St. Nikolai of Ohrid and Zhicha, The Prologue of Ohrid, Lives of Saints Hymns, Reflections and Homilies for Every Day of the Year, edited by Bishop Maxim, Volume 1, Sebastian Press, Alhambra, CA, 2017.

As a birth attendant who sees that work as very sacred indeed, I was really blessed by Blessed Olga of Alaska’s story. Thank you for linking to it.

Thank you for sharing your experience ! I learned a lot about St. Nectarios through Man of God. I’d love to see more lives of the saints told through the medium of film.